Brazil (dir. Terry Gilliam, 1985) - Review

Download the Brazil screenplay for personal, private use.

Defending his ‘Trilogy of Imagination’, Terry Gilliam argued that “I think there are a lot of people who assume that, because the films are so visually rich, that there's nothing inside…There’s too much cake and too much frosting for them… But I can make it and I can consume it” (Chicago Tribune, 1989).

Like much of the dystopian sci-fi genre, the second film of the trilogy, 1985’s Brazil, has grown less tantalising over the decades due to its convergence with science fact. But while elements of the plot may have lost their novelty — particularly the government ministers trumpeting buggy tech — Gilliam’s gluttonous banquet of visual richness has not. Contemporary viewers may find themselves identifying a little too closely with downtrodden protagonist Sam Lowry, seeking his escape from the surveillance capitalist hellscape in an audio-visual dreamland of yesteryear.

Co-writer Tom Stoppard characterised the film as “the myth of the free man in an un-free society”; however, as evidenced by the number of bust-ups over rewrites by Stoppard and others, Brazil does not foist a singular interpretation on the viewer. As visual effects supervisor Julian Doyle put it, “it’s harder for people to say what this film is about because you’re being smashed in the head by all these visuals” (both quoted in What is Brazil?).

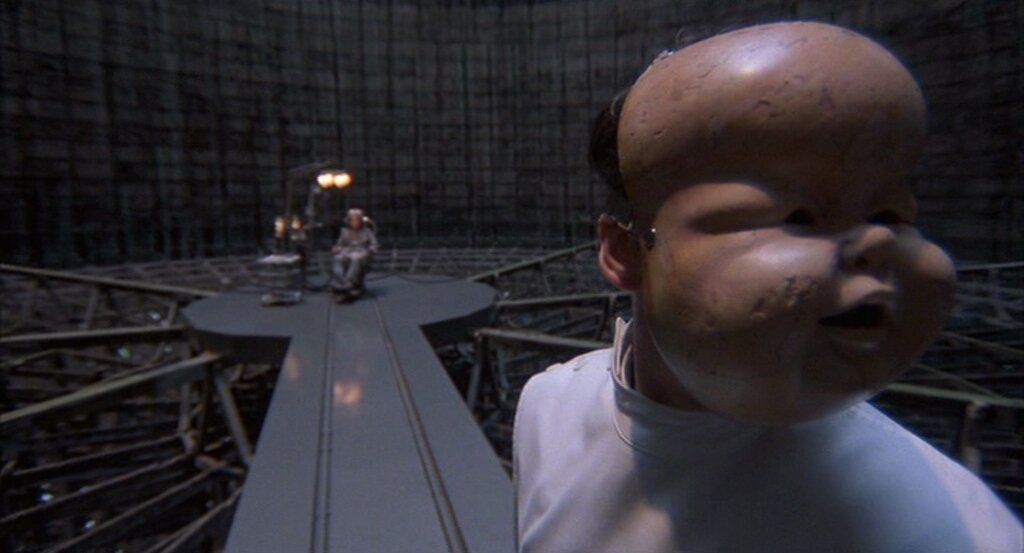

In the film, Sam Lowry (Jonathan Pryce) works in a dystopian, bloated version of the Civil Service, nepotised between jobs by his socialite mother, and taking refuge from the bombings and bureaucracy of daily life in his fantasies. His orderly existence collapses with the intrusion of Jill (Kim Greist) — the literal woman of his dreams — and rogue plumber Archibald Tuttle (Robert De Niro), who induct him into a paramilitary resistance. Flights of Oedipal, ideological, and aesthetic fancy punctuate the absurdist plot, sprinkling Kurosawa-inspired monstrous samurai and hordes of murderous dolls amongst pastiches of British high society and office culture.

Gilliam’s vision of inefficient British totalitarianism has uncanny parallels with, for instance, its stumbling response to the Coronavirus pandemic — although at least the Moderna corporation featured in Gilliam’s previous film doesn’t appear in Brazil. “In a free society, information is the name of the game,” bumbles the Deputy Minister of Information, defending his fruitless terrorist tracking programme with a slew of cricket analogies. “And the cost of it all, Deputy Minister? Seven percent of the gross national produce…” More broadly, the callous, clunking bureaucratic machine inflicting both suffering and paperwork on the disadvantaged recalls recent outcries over (m)algorithmic selection biases.

The film borrows the visual language of optimistic sci-fi pieces like Star Wars or Star Trek only to stymie it with references to the thirties and forties, from the fascist architecture to the title song, which serves as a leitmotif of thwarted escapism. A 1930s popular tune haunts the film in various arrangements, from the orchestral to the eight-bit, as an ironic and constantly reimagined contrast to the dull, oppressive (and emphatically British) reality. Posters lifted from real World War II or Soviet propaganda campaigns are re-captioned with quips like ‘Loose Talk is Noose Talk’, and the underground army of civil servants watch Casablanca to procrastinate. Tom Stoppard’s trademark absurdist existentialism is evident in the shock troops, who saw through a Dickensian family’s humble roof and seal the father into a rubber sack, never to be seen again, but provide his wife with a receipt.

Only the Harrods chintz of the upper class — Sam’s mother (Katherine Helmond) and her crew of plastic surgery-obsessed biddies — disrupts Gilliam’s vision of English life, refusing to let a bombing fluster their lunch. Meanwhile, as guilt creeps into Sam’s fantasy world, it takes on the tone of Walter Mitty on a bad trip: “it’s gonna be horrendous”, chuckles Doyle in the making-of feature, setting up a room packed with rolling resin eyes.

Despite a demanding two-and-a-half-hour runtime, and moments of overindulgence, Brazil offers its audience visual spectacle, postmodern navel-gazing, satirical black comedy, and existential horror. In any case, Gilliam’s intricately worked sensory overload offers both a depiction and a self-referential respite from the struggles of the individual under late-stage capitalism.

Áine Kennedy is a London-based writer and manager of the ScriptUp blog.