Grave of the Fireflies (dir. Isao Takahata, 1988) - Review

It may come as a surprise to hear that Grave of the Fireflies was produced concurrently, and released as a double feature, with one of Studio Ghibli’s best-known and best-loved works, My Neighbour Totoro. Less surprising, though, that audiences reportedly developed a habit of leaving the cinema after Totoro to avoid the profound depression induced by its companion piece.

While both works hinge on childish innocence and imagination, Grave of the Fireflies employs the medium of anime to unconventional ends. Totoro, and many other beloved Ghibli works, use animation to depict the rich, otherworldly possibilities of youthful fantasy, which evade capture in the blunting literalism of live action film. Grave of the Fireflies is an unflinching survey of how innocence and imagination- in a word, the nostalgic, pure-hearted escapism with which Studio Ghibli is synonymous- cannot protect the innocent from suffering.

Totoro and its title character- an inscrutable rabbit-spirit, not unlike a benevolent and morbidly obese version of Frank from Donnie Darko- inhabit a pastoral utopia, seemingly untouched by the war, an amalgamation of every rose-tinted countryside memory from a happy childhood. Meanwhile, Grave opens with the spirit of the 14-year-old protagonist looking on as his own corpse is robbed by a train station janitor.

Set in Kobe in 1945, during the last gasp of World War II, Grave examines the complexity and injustice of the effects of war on its less-remembered victims. After the Enola Gay bombed Hiroshima in August 1945, its pilot, Paul Tibbets, became a national hero in the US, celebrated for ending the conflict. "I'm proud that I was able to plan it and have it work perfectly as it did... I sleep clearly every night,” remembered Tibbets in 1945, adding three decades on that “we knew it was going to kill people right and left. But my one driving interest was to do the best job I could so that we could end the killing as quickly as possible.” The mastery of Grave of the Fireflies lies in undermining this dehumanising binary, with its narrative of logic and efficiency, and in sapping the bounds between other apparent polarities in postwar popular culture: it juxtaposes childish joy with adult suffering, the monstrous ‘Japs’ with the ‘good guy’ Allies, the animated fantasy with the real-life story on which the film is based, to deliver a more nuanced, and deeply affecting, record of a time which is difficult to understand in its distant historical context.

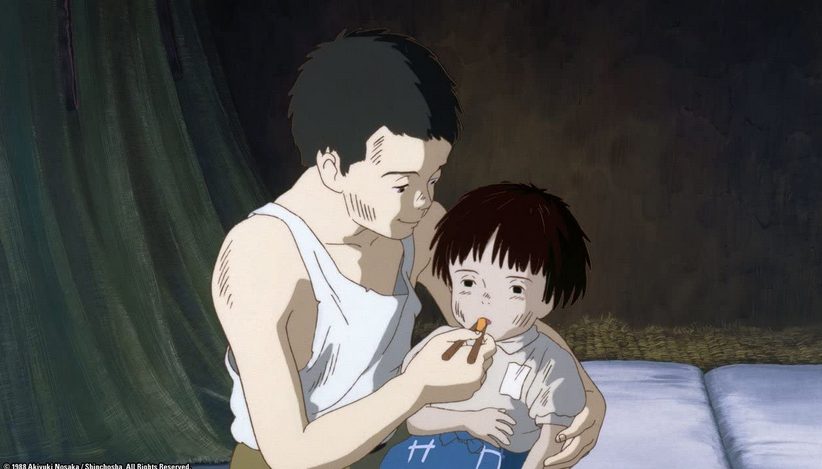

14-year-old Seita, and his 4-year-old sister Setsuko, live in Kobe with their mother; their idolised father serves afar as a Navy officer. Their bucolic, candy-hued life- soundtracked by a uniquely haunting score by Michio Mamiya, and by the jarringly authentic voices of real child actors- fractures with the intrusion of the regular air-raid siren, which, this time, dispatches both their entire village and their mother. Seita must shoulder the responsibility of providing for his sister whilst attempting to keep their mother’s death a secret, struggling at first with the demands and resentment of an aunt who takes them in, and fundamentally with the powerlessness of fantasy and innocence against the brutal reality of wartime.

The film uses aspects of Ghibli’s classic magical realism: the fairytale unity with nature, most evident in the orphans’ bond with the heavily symbolic fireflies, but also in the lakeside grotto to which the siblings flee from the heartless adult world; the visions of Japan’s past military glories which arrange themselves on Seita’s mosquito net; and, most hauntingly, the arrival of the children’s spirits to their final destination, a bench overlooking the now-modernised city of Kobe, where they died alone in 1945. But the ‘magical’ aspects highlight the fact that these moments of comfort and reassurance are just that- fantasy conjecture applied to the ‘realism’ of an overwhelmingly harrowing narrative, borne of author Akiyuki Nosaka’s desire to "compensate for everything I couldn't do myself" in the events which inspired the film. Nosaka based the original story on his own experience of the firebombing of Kobe, after which, just as in the anime, his sister died of malnutrition in his care. The death of Seita in the film, which allows him to reunite and reconcile with his sister’s spirit in modern-day Japan, provides the fictional and imaginary closure- a return to the refuge of childhood innocence synonymous with the Ghibli mode- so deeply and awfully absent in lived reality.

Seita embodies not only the author’s personal shame, but that of a wider national consciousness; perennially sporting a quasi-military uniform which highlights the frailty of his childish body, Seita falls prey to selfishness, stubbornness, and misplaced nationalist fervour. He refuses to beg for his aunt’s hospitality or his mother’s bank savings to save his sister’s life, until it is too late; he fantasises about his father taking armed revenge on both the outsiders who bomb their home, and the community members who exploit them. Fundamentally, the nuance with which the film explores a volatile and painful period of history memorialises it in an unusually meaningful way: by engendering thought and reflection, love and remembrance rather than the kind of singular, jingoistic narrative which wrought so much destruction in both the film and in real life.

Áine Kennedy is a London-based writer and manager of the ScriptUp blog.