Man On The Moon (dir. Milos Forman, 1999) — Review

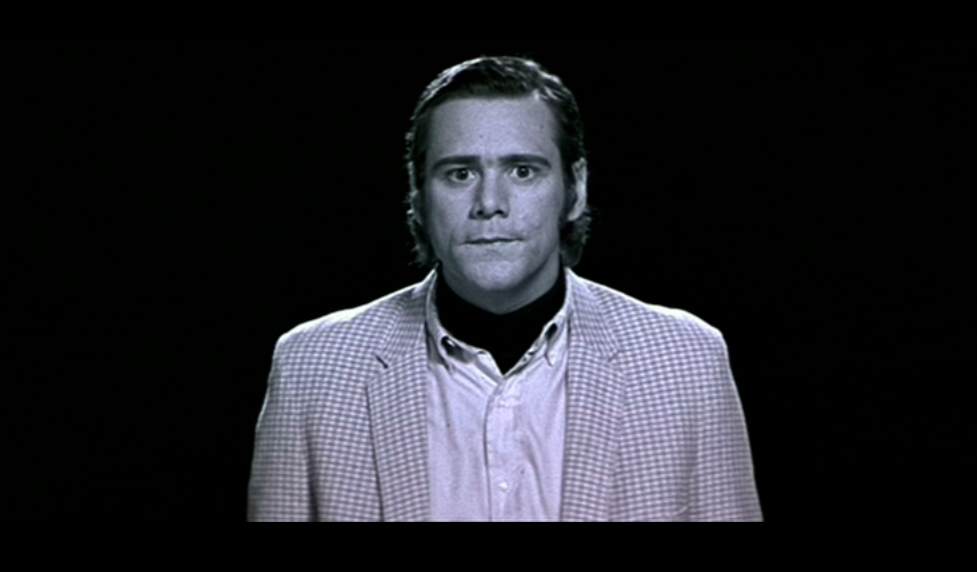

Volatile stand-up-comedian-cum-situationist-hoaxer Andy Kaufman is remembered primarily through his squeaky-voiced Latka in the 80s TV sitcom Taxi. But, as Milos Forman’s biopic takes pains to remind us, he led a spicier double life as a a cult figure ransacking Middle America through anarchic live performances on SNL, David Letterman, and the college circuit- or through his alter ego, the appalling lounge singer Tony Clifton. Jim Carrey, in a solemn and conspicuous act of ancestor worship, plays Kaufman, with Forman making a valiant return to his familiar themes of madness and creative inspiration despite the comparative paucity of his subject. The film does several slick, zesty sleight-of-hand sketches of comic genius: Kaufman dying on stage at the Improv club; cut to shot of audience looking baffled and irritated; cut to shot of Kaufman ploughing on; cut to audience smiling, shrugging, starting to laugh. And afterwards,Kaufman's agent George Shapiro (Danny DeVito) chuckles prescriptively: "You're insane! But you might also be brilliant!". You don’t say; unfortunately, this argument doesn’t ring with the conviction that Forman’s giggling ninny Mozart could muster.

Charting Kaufman’s path from New Jersey to to the crowd-baiting outer limits of the comedy frontier, the film relies on a succession of sounding boards- not just DeVito, but Kaufman’s writing partner and co-conspirator Bob Zmuda (Paul Giamatti, looking somehow 42 and 12 years of age at once). The discomfiting ugliness and aggression of Andy Kaufman’s comic characters manifest in a perplexingly unexplored kink: his habit of wrestling women, including Lynne Margulies (Courtney Love). In one of its clearest spells of self-confessed dramatic licence, the film turns Lynne from a snarling feminist- pulled from the studio audience for an unceremonious battering- to saintly soulmate, in sickness and health. Love’s performance seems all the more impressive considering it came on the heels of both Kurt Cobain’s suicide and her own heroin addiction; a tall order to play the sane and stable half of a romantic pairing, but she excels.

Man On The Moon remains within a complimentary tone of respectful, bittersweet drama as a showcase for the implied comic genius, allowing latter-day viewers to marvel at his success in the puritanical echelons of American network television. It does remain remarkable how far Kaufman was allowed to go: mad stunts on air, attacking and humiliating the audience, "a single-minded pursuit of anarchy" from which he apparently remained unseduced by a parallel career in a top-rated, family friendly network show. (Most of the original cast of Taxi appear in the film, unsmilingly enduring once again the trial of looking like pedestrian schmucks compared to Kaufman- costar DannyDeVito, who has interestingly promoted himself out of the Taxi cast to play someone in on the gag.) But this wild and crazy guy died from lung cancer at the age of 35, a career move which took him into the realm of legend and away from a sad life of Netflix original romcoms.

What could and should have been interesting about Andy Kaufman's life is how he reacted to failure: he had hardly reached the top when public and fellow artists alike wearied of being his straight man, and turned against him. He was getting bad press and voted off Saturday Night Live in a viewers' phone poll that Kaufman clearly believed he would win: a rare stunt which he could not control.

But Carrey plays Kaufman the same throughout, in good times and bad, with no growth and no progression, with the same blinking, moon-faced detachment, a sort of halfway-house between Kaufman's weird, deadpan live act and an assumed professional backstage reserve. One of Kaufman’s truly astonishing traits was his self-appointed role as World Inter-Gender Wrestling Champion, at the time considered the quintessence of being on the comedic skids. But now, in its magnificent lack of taste, it looks like an inspired take on the sex wars, but sadly Forman didn't expand this gloriously offensive part of Kaufman's career, or his furious sister’s suspicions of his staging the ultimate, bad-taste stunt with cancer.

Forman hints at an Elvis-style resurrection for Andy, suggesting that he might actually have faked his death after all. By this assumption, Andy Kaufman is up in Valhalla with fellow deceased SNL star John Belushi, while survivors Chevy Chase, Dan Aykroyd and Eddie Murphy labour in the world of mediocrity below. Guided by screenwriters Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski, Forman doesn’t examine Kaufman as an artist or explore him as a man; rather, he genuflects to a prankster ordained the King of (Conceptual) Comedy for such “subversive” stuff as comedic whoremongering and nonsensical performance art. While the film’s greatest pleasure derives from the ardent glee Jim Carrey takes in impersonating his hero, Forman’s curtain closer, a tear-jerking final concert in Carnegie Hall, seems a very tame ending for his objectionable comedy guerilla.